Sometimes, the idea of all individuals being equal can be difficult to believe. The news constantly tells us of the ‘evil’ taking place within our own borders and far beyond. Social media, search engines and the echo chambers they create ensure we constantly have enemies – there are battles between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ to be found everywhere.

Even those who attempt to ignore problems beyond their immediate world know through the grapevine what the current perils of the world are and who’s to blame.

It seems that clearly, some people are better than others when it comes to intentions. Some people are only out for themselves while others go out of their way for others. And if people choose to do bad things, how are they not bad?

Well, it’s not as simple as that.

People can do bad things and still not be inherently ‘bad’ people. Faced with the same life circumstances from birth, you’d be surprised how similarly to the ‘bad’ people you might think and behave.

Under the right conditions, all humans have the potential to do very bad things. But all humans also have the potential to change, grow and do very good things regardless of their past – under the right conditions.

It might help to have some idea of why you are the way you are – and why everybody else is the way they are for that matter.

We’re not so different, you and I.

Our Motivation and Reward System

How we behave and think is largely shaped by our environments during our formative years. How we perceive our experiences has a significant impact on our thought processes, actions and outcomes in adulthood. This is why, even though we all fundamentally have the same motivation and reward system, our lives and perceptions can appear so different.

What we find rewarding is largely shaped by our early life experiences and perceptions, which in turn motivates us to do the things we do.

Most animals possess motivation and reward systems that drive behaviour. For example, animals respond to perceived rewards by engaging in behaviours that fulfil their needs, such as finding food when hungry or fleeing from predators to avoid being food.

In most mammals, two neural circuits, the mesolimbic reward system and the social behaviour network, are thought to be mostly responsible for reward-seeking behaviour.

The mesolimbic reward system is a neural pathway that transports dopamine from the ventral tegmental area to the amygdala, nucleus accumbens and hippocampus, which is why dopamine is commonly thought of as our natural feel-good chemical (even though dopamine is more to do with anticipating rewards than actually receiving them).

In humans, our motivation and reward system functions similarly but is influenced by our higher cognitive abilities. Our intelligence allows us to find a vast array of things rewarding, extending beyond immediate survival needs to include complex social and cultural rewards (that in turn satisfy more fundamental survival needs).

Different people can also perceive the same thing in countless ways – what’s considered ‘good’ by some people can be considered ‘bad’ by others.

While it may be difficult to understand, the fundamental mechanisms that drive what you perceive to be bad behaviours in others are the same fundamental mechanisms that drive what you perceive to be your good behaviour.

During our formative years, while biology plays a role, the environments we’re exposed to largely dictate what we find rewarding as adults – unless we intervene and expose ourselves to new information and perspectives with an open mind.

We like to think life is as simple having thoughts and acting on them based on ‘knowing what’s best’, but our mind isn’t the true controller of the entire living being that we are.

You can find out why this knowledge is so crucial to understanding the true nature of addiction by reading my in-depth personal guide to overcoming alcoholism.

The Reality of Mind-Body Unity

The mind doesn’t control the body, nor does the body control the mind. Our thoughts are simply the brain’s way of making sense of everything that’s happening to the entire organism.

This unified mind-and-body system is powered by an array of incredibly complex processes, all working as one to achieve goals based on what it perceives to be rewarding.

In reality, we don’t have a ‘unified mind-and-body system’ in the sense that we’re made up of two core components that power the entire being. The entire living being that we are is powered by a countless array of bodily and cognitive processes, and our ‘mind’ is an emergent feature of them.

Many studies suggest that our conscious awareness actually catches up with the decisions our entire dynamic system has made with a streamlined narrative of what the interconnected regions of our brain have already decided (the research isn’t conclusive yet).

Read our article on quantum mechanics, quantum consciousness and free will to see if we have any control over our futures whatsoever.

The Illusions of Our Mind

One of the biggest obstacles to perceiving the true nature of our reality is our sense of self, often experienced as a first-person inner monologue.

While this internal dialogue helps us make sense of our experiences and navigate the world, its existence doesn’t imply that we choose its content out of our own volition or that it controls our actions – even if it seems that way.

Complex language skills are acquired rather than inherited. While you’re innately equipped with the cognitive abilities to develop them, complex language skills are not a given. We may associate our sense of self with our inner monologue, but our sense of self – a survival tool enabling us to distinguish ourselves as individuals in our chaotic environments – doesn’t depend on it.

If complex language and our inner monologue are acquired rather than innate, we can deduce that our inner monologue is not the source of our sense of self – it is a byproduct of it. How we perceive our ‘self’ is a result of cultural, social and biological factors.

How we perceive ourselves as completely autonomous is also illusory in nature. Read our article on the autonomy illusion to find out how seeing through it can unlock self-awareness, self-compassion and empathy.

Nature vs. Nurture

When it comes to down to it, all humans have the same or a very similar ‘operating system’ on a fundamental level. While genes undoubtedly play a role in who we become, our personalities are almost entirely created by our environments. That includes how you behave and even think.

After all, even language is acquired rather than inherited – your first-person inner-monologue is not a given or even a prerequisite for your survival.

Your biological makeup may predispose you to certain behaviours, but how they manifest depends on your environment, particularly during your formative years. The language you speak, clothes, music and movies you like, and how you connect with others are all significantly shaped during your formative years, especially between the ages of 0 and 7 years old.

Genes, though, also play an important role in how you perceive your experiences, which has a dramatic impact on your future outcomes. People who are naturally more emotionally sensitive than the average person face an increased risk of developing depression and anxiety. But many people who are naturally sensitive simply grow up to be kind, caring and productive adults – if their development was nurtured healthily.

Read our guide on nature vs. nurture to find out why we think nurture ultimately wins the debate when it comes to thoughts and behaviours (and why that’s good news).

Narcissism in Individuals

Sometimes, we think narcissistic or sociopathic people are ‘evil’ or born bad. Again, while genes may predispose people to what may be deemed narcissistic attitudes and behaviours, depending on your culture and values, our environments play a huge role in how those attitudes and behaviours actually manifest.

There’s a fine line between healthy pride and an inflated ego. And an inflated ego doesn’t necessarily make somebody a ‘narcissist’ in the clinical sense.

Many studies on twins suggest that genetics play a more significant role in the development of narcissism than we’re giving it credit for.

A meta-analytical review published in 2018 by Cai and Luo, “The Etiology of Narcissism: A Review of Behavioral Genetic Studies” presents data from a number of studies on twins to determine whether genetic or environmental factors play a bigger role in the development of NPD. Livesley, Jang, & Vernon (1998), for example, found that 44% of the variation in NPD among individuals can be attributed to genetic factors.

Kinder et al. (2008) revealed more moderate findings, suggesting that 37.3% of NPD is attributable to genetic influences. In the other direction, Torgersen et al. (2000) suggested that 77% of the variance in NPD can be attributed to genes.

But from our perspective, studies on twins must be taken with a pinch of salt.

Many studies, not just on narcissism but also addiction and a range of other mental health conditions, focus on twins separated at a very young age. The rationale is that if both twins exhibit similar behaviours or conditions, genetics must play a key role. But the extenuating circumstances behind twins separated at birth must very often surely have a dramatic impact on their likelihood of developing a range of conditions, regardless of their genetics.

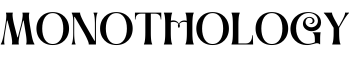

Essentially, from the Monothologic perspective, narcissism can largely be attributed to an underlying fragility in self-esteem – or more accurately, the behaviours that overcompensate for it.

Fortunately, the fact that our attitudes and actions are, for the most part, culture- and context-dependent learned behaviours means they’re not set in stone and can be altered.

Thought Experiment

Imagine you were adopted into a middle-class family, with parents entirely focused on climbing their career ladders and improving their standing in society. You’re 12 years old, just about to start high school. From the outside, you have it all. All your toys are the envy of other kids, you turn up to school in a sports car, and your parents are well-known.

But your parents are also busy. You’re never alone as you have a nanny, who your parents chose based on her strict Christian morals and ability to nurture well-disciplined, well-to-do professionals.

You’re punished for being immature – no running around the garden or watching TV. Your entire life is timetabled, and punishment entails for making a sound when it is deemed inappropriate. From time to time, you encounter your parents, who explain their expectations of you with regards to your performance and attitude.

The children at school don’t like you. You’re considered an outsider, and many kids are jealous of your possessions. As you grow resentful of these children, you flaunt your possessions more often – you’d rather have their jealousy than their ridicule.

Your parents praise you for your good grades. It’s the only validation you receive from them, and you let your peers at school know how special you are. You don’t make any friends, but your grades and family finances ensure your position in a prestigious high school. Here, your sense of worth remains dependent on high grades and possessions. Only, the other children here also derive their sense of worth from high grades and possessions – it’s cut-throat competition from here on out.

Eventually, you become a politician based on your personal successes and possessions, making decisions on behalf of those who once ridiculed you. Do you put their needs first?

‘Bad’ Groups – Collective Narcissism

Psychologically, collective narcissism arises from the same roots as individual narcissism – an underlying insecurity or fragility in self-esteem. People may turn to group identification to bolster their self-esteem, projecting their unmet needs for validation and recognition onto the group.

Sociologically, collective narcissism is often fuelled by social, political or economic instability, which can heighten the need for group cohesion and a sense of superiority.

All humans have a fundamental need for validation. When they can’t get that validation for being who they truly are, they’ll often attempt to be somebody else, leading to all sorts of problems. For starters, our mental and physical health won’t stand for our delusions and state of denial in the long run (read “The Body Keeps the Score” by Bessel van der Kolk) . But we’re also highly susceptible to exploitation and manipulation without a healthy sense of belonging.

Without a true sense of belonging and the need to find one in some form or another, people become susceptible to narcissistic groups ranging from cults and gangs to extremist factions. It’s easy to think we could never be susceptible to such exploitation due to our inherent goodness, but this isn’t how the human animal operates.

Thought Experiment 2

At the age of 12, you’ve lived in the UK with your parents for seven years. You moved here from Baghdad to escape war and persecution due to your Shia Muslim faith. After losing three siblings and your school to war, your parents attempted to save your life.

You try to fit in at British school, but many kids make fun of your accent. Also, some children tell you that all Muslims are scary terrorists, and you notice their parents stay out of your way. It seems like even some teachers give you funny looks when they assume you’re not looking.

Attempting to fit in, you start wearing trendy clothes and listening to hip hop music, severely disappointing your parents. At school, you’re bullied and feared. At home, you’re punished, criticised, and told you’re a disappointment to God.

Eventually, you meet some ‘traditional’ Sunni Muslims online who treat you well. They teach you that it’s not your parents’ fault – they’re just confused by the wrong lessons of Islam. But they warn you that Western culture will deem you to hell if you allow yourself to become too embroiled. You also learn about the UK’s involvement in the invasion of Iraq, leading to conclusions that the UK (and the entire population it represents) was responsible for the death of your siblings and bombing of your school. Fortunately, you can discuss all your needs, concerns and worries with these people who truly care about you and have all the answers to your deepest needs and pain.

Where do you see yourself in six months?

How Do We Stop Bad Things Happening?

Ultimately, the world is not within any individual’s control. Our formative years have a tremendous impact on our thought processes and behaviours as adults, and there’s nothing any one of us can do to ensure each and every human receives a healthy and nurturing childhood that leads to the development of a healthy ‘operating system’.

But we’re fortunate – our operating systems are adaptable. Our neuroplastic brains can take in and digest new information, changing the way we think if we open our minds to it. We’re also an intelligent social species that’s equipped with the ability to provide each other with a sense of belonging.

If we understand our operating systems, we can better understand why people do the things they do in place of judgement and ignorance, enabling us to react more constructively and objectively. In order to do this, we must see through our illusion of autonomy so we can retake as much as possible of the control we do have over our lives and our future.

This article has been adapted from the book, Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation, which explores concepts ranging from neuroscience and evolutionary biology to the latest empirical research in quantum consciousness to dispel the human autonomy illusion and peel back the layers of the bigger picture of our existence. By understanding the illusions created by our minds, how we really operate as humans, and how to reflect objectively, Monothology helps you unlock self-awareness and boost emotional resilience.

Monothology presents a non-religious explanation of ‘God’ as the universe emerging, with our ‘Sense of God’ described through the lens of biology and evolution as an emergent cognitive function. It discusses how existing research suggests this Sense of God could be the origin of both religion and science.

We also explore the nature of free will, personal responsibility, mental health, increasing societal narcissism, and the meaning of life through groundbreaking and established research in neuroscience, evolution, quantum consciousness, particle physics, behavioural psychology, and much more.

Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation is available to purchase now at the Amazon Kindle Store for $9.99.

0 Comments