We like to believe we’re in full control of our actions and outcomes. We have a thought, and then we do something. We deliberate in our heads before coming to a decision and taking action. And we think in terms of ‘I’ when it comes to our wants, needs and goals. It seems almost irrefutable to suggest that the mind doesn’t control the body.

However, the mind doesn’t control the body, nor does the body control the mind. They work in tandem as one dynamic system in constant reaction to its internal states and environment.

In terms of what really dictates your actions, it’s much like the automation of a sunflower opening its petals on a sunny day – humans are just much more complicated in how their organic processes react to the environment to maximise the chances of survival for the entire being.

But what about freedom, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? If human autonomy is an illusion, are they all meaningless lies?

No – plenty of evidence suggests that you do have some control of your actions and outcomes.

But before you can retake as much of that control as possible, it’s essential to see through the illusions created by your mind.

The Illusions of the Inner Monologue

One of the biggest obstacles to perceiving the true nature of our reality is our sense of self, often experienced as a first-person inner monologue. This inner narrative creates an illusory perception of complete autonomy, accountability and control.

From an evolutionary perspective, having a sense of self allows us to navigate the world as individual living organisms with specific needs and goals, separate from everything else in our environment.

This self-awareness enables complex living organisms to quickly and effectively respond to internal needs and environmental stimuli. For instance, when faced with danger, we can react near-instantly without consciously deliberating over which limbs to move and in what order, the distance between us and obstacles, adjusting our heart rate, etc. Instead, we can focus our conscious attention on a single goal that maximises our chances of survival.

Rather than being a separate entity, the sense of self is an emergent feature of our overall system that helps us make sense of our lives as one cohesive narrative. This allows us to react to our ever-changing needs and environment almost instantaneously.

Our sense of self is intricately tied to an inner monologue, the continuous stream of thoughts we usually experience from a first-person perspective (‘what should I do today?’).

However, while this internal dialogue helps us make sense of our experiences and navigate the world, its existence doesn’t imply that we choose its content out of our own volition or that it controls our actions – even if it seems that way.

When the living organism that we are engages in deliberation, self-reflection and articulating experiences, it’s a response to our internal needs and environment, and multiple areas of our brain are engaged simultaneously. Our inner monologue arises, or emerges, from the interplay of these interconnected brain regions. But it doesn’t control them – it’s the other way around.

Case in Point: ADHD

ADHD can impact the brain’s Default Mode Network (DMN), a network of brain regions that’s active when you rest. It’s also behind most of your daydreaming.

The DMN of a brain with ADHD is often overactive, resulting in frequent spontaneous thoughts that make it challenging to focus on one task or thought for extended periods.

The inner monologue, which many of us perceive as the driver of our actions, is heavily influenced by these underlying brain processes. For someone with ADHD, the brain’s natural inclination to seek novelty and stimulation significantly impacts this inner dialogue. The constant search for new and interesting stimuli can make it seem as though one is deciding to switch tasks frequently or think about random things. However, these shifts are not conscious choices but reflections of the brain’s attempts to find rewarding and engaging activities.

The Evolution of ‘Self’: From Collectivism to Individualism

In ancient times, early humans often interpreted their inner experiences, including their thoughts and feelings, as manifestations of external influences or guiding principles.

These interpretations were not necessarily misguided but perhaps reflected an innate awareness that our conscious thoughts do not arise of our own volition. They perceived their thoughts and actions as guided by external sources, which may have been a way to grapple with the uncertainty of their existence.

As societies evolved, so did our understanding of the self and control. While early human societies often emphasised collective or external frameworks for understanding identity and agency, the development of philosophical thought and scientific inquiry introduced the idea of the ‘self’ – an autonomous entity with personal control over its actions. This shift marked a move from viewing identity as largely shaped by external factors and communal roles to focusing on individual autonomy and personal agency.

This perception has a significant impact on how we understand personal responsibility and moral judgment. It also largely overlooks the broader context of environmental influences and innate processes.

Our inner monologue may be a reflection of intricate brain processes, but the form it takes is a cultural phenomenon rather than an accurate representation of reality.

Sense of Self Acquisition

If complex language skills are acquired rather than inherited, then it follows that our sense of self is also influenced by these acquired skills, given that many people associate their sense of self with the first-person narrative of their inner monologue.

As we know that complex language and our inner monologue are acquired rather than innate, we can deduce that our inner monologue is not the source of our sense of self – it is a byproduct of it. How we perceive our ‘self’ is a result of cultural, social and biological factors.

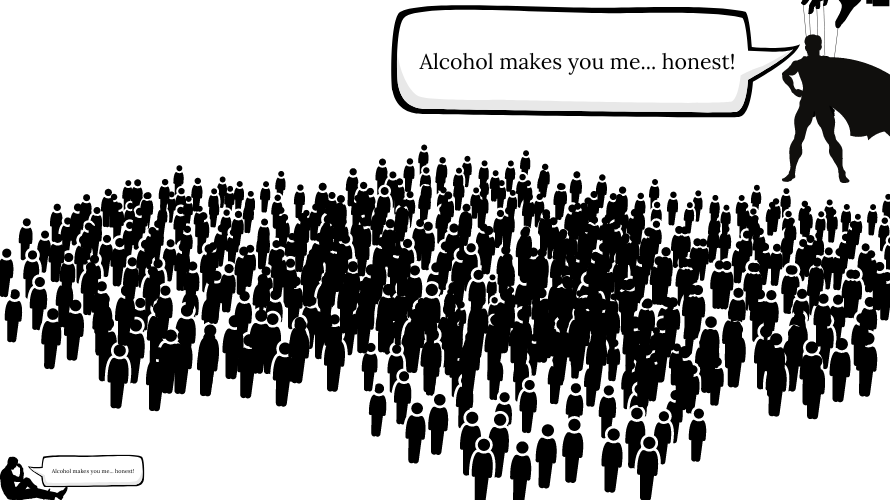

People often believe their control over their inner monologue contributes to their good behaviour, assuming that their ability to manage internal dialogue makes them morally upright. Conversely, they tend to view those who behave poorly as choosing a flawed inner monologue, leading to judgments of inherent badness.

I.e., if somebody thinks before committing an atrocity, then they must be a ‘bad’ or flawed human being, different to everybody else.

On the surface, this may seem to make sense. However, this perspective is illogical.

As we’ve discussed, our inner monologue emerges from complex brain processes that are largely dictated by internal states, whether we like those internal states or not. Believing we all choose our thoughts and subsequent actions simplifies morality and behaviour, and goes against the science. By focusing solely on perceived control, we overlook the significant role of external influences and developmental experiences in shaping behaviour.

There’s No Such Thing as a Bad Egg

The nature versus nurture debate delves into whether genetics (nature) or environment (nurture) plays a bigger role in shaping behaviour and personality.

While both elements are interconnected and influence each other, evidence strongly supports that environmental factors often have a more profound impact on behaviour than genetic predispositions. As discussed, even language is acquired rather than inherent.

Genetic predispositions can influence the likelihood of developing certain behaviours or mental health conditions, but they do not predetermine outcomes. The environment in which an individual is raised dictates how these predispositions manifest. For instance, a person with a genetic tendency towards anxiety may only develop an anxiety disorder if their environment is stressful or unsupportive. On the other hand, a nurturing environment may mitigate these genetic risks, leading to healthier behavioural outcomes.

Shunning people we perceive to be ‘bad’ is a failure to recognise what powers us as human beings – and it isn’t our sense of self or our internal monologue. Labelling individuals as ‘bad’ fails to address the underlying issues and perpetuates a cycle of blame and misunderstanding. Acknowledging that no one is born inherently ‘bad’ by understanding what really drives human beings naturally unlocks a more compassionate and constructive outlook.

Nobody is Born a Saint

Just as our illusion of autonomy makes us vulnerable to looking down on others for perceived failures and ‘evil’ actions, we’re also susceptible to viewing others as superior due to their perceived successes. This false perspective of complete autonomy can lead people to compare themselves unfavourably to others, resulting in emotions such as jealousy, self-loathing and worthlessness, all major factors in a range of mental health conditions.

Because we believe that we have control over actions with our inner monologue, we often believe that the positive outcomes of others reflects an inner thought process that makes them an inherently good person with moral superiority. As we’ve seen, the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ is less about inherent qualities and more about the influences that shape our development.

The processes that drive and influence behaviour are universal and apply to all individuals. Whether one is perceived as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ the brain’s functioning and its response to stimuli are fundamentally the same. The key difference lies in the experiences and information to which we are exposed. These experiences shape how our brain processes information, which determines our thought processes and our actions.

It is entirely natural to be inspired by individuals who seem to embody positive qualities. However, these individuals are not fundamentally different from others; they have simply benefited from experiences that guided their development in a positive direction. Their achievements and behaviours are the result of favourable conditions rather than intrinsic superiority.

When we are inspired by someone, it might make more sense to focus on their actions and the contexts that led to their positive behaviours, rather than assuming these actions stem from inherent goodness.

Unlocking Self-Compassion

The illusion that our inner monologue drives our behaviour leads to self-blame when things go wrong. We think that if we could just control our thoughts and actions better, we would be different. This belief can result in negative feelings of self-loathing and inadequacy, as we berate ourselves for failing to meet these self-imposed standards.

However, embracing the idea that our actions are a reflection of our brain’s processes—shaped by our experiences and the information available at the time—can transform this perspective. At any given moment, the living organism that we are is acting in a way that it believes is best for its survival, based on the information it has. This understanding can free us from the cycle of self-blame and allow us to approach ourselves with the same compassion we would offer to others.

Instead of focusing on self-criticism (why am I so stupid?), analyse what led to your decisions and behaviours (why did that stupid thing happen so that I can avoid it next time?). Understand the context in which you acted and recognise that you were doing what you believed was best at the time. This process helps you to separate your actions from your self-worth and allows you to identify areas for growth without judgment.

Boosting Self-Reliance and Resilience

Our sense of self enables us to navigate the world, respond to our needs and desires, and protect ourselves from danger. However, when we identify our personal identity as our entire sense of self, we may feel like an attack on it is a genuine threat to our survival.

Having a culturally influenced and context-dependent personal identity achieves survival goals such as social cohesion and personal fulfilment. However, personal and collective identities are cultural phenomena, and no two are the same.

By being an authentic person, you will undoubtedly be disliked by many people you encounter. But you’ll be liked, valued and appreciated by many, many more. Often, encountering people who dislike your honest opinions (assuming they aren’t hateful) can feel empowering – it’s just proof that you’re being true to yourself.

Differences in opinion often don’t merit any further action than a simple disagreement. If we see through our autonomy illusion, we can stop perceiving alternative views and even, in some cases, verbal abuse as threats to our sense of self and very survival.

Separate your sense of self from your personal identity. Protect your sense of self from genuine dangers – bond with people over your personal identity and the differences between yours and theirs. Avoid seeking validation from others and feel grateful when you do receive external validation for simply being yourself. When others attack, belittle or berate your views, recognise your personal identity does not depend on their validation, and your sense of self is not in real danger. See through the autonomy illusion to quickly understand that those who try to cause genuine offence are masking their own insecurities and inner pain. How you respond (or don’t, as is often best) is up to you, but realigning your perspectives with a more accurate understanding of our shared existence will undoubtedly alter your reactions for the better.

Unlocking Self-Awareness

One of the biggest pitfalls of psychiatry and self-help books is that they largely depend on you being able to accurately and objectively make sense of your experiences. However, many mental health problems stem from difficulties during childhood. In those formative years, we form core beliefs that – unless challenged – hold significant sway over our thought processes, actions and outcomes. This is why so many mental health problems are rooted in our early life experiences, particularly unresolved trauma.

If we are unaware of our unresolved trauma, repressed emotions and internal conflicts, psychiatrists may misdiagnose mental health conditions based on the information we provide. After all, nobody but ourselves is capable of recalling the events of our life story as we actually perceived them as children. However, we may convey our experiences from the same perspective that we’ve held since childhood, completely unbeknownst to the fact that we’ve lived in denial for decades.

If we are unable to accept our negative emotions during childhood because of our dependency for survival, we may retain delusional beliefs of certain people’s actions and intentions throughout life. We simply can’t bring ourselves to accept that those who were supposed to care for us may actually be bad people, so our psychological mechanisms ensure that our true thoughts and feelings remain repressed, manifesting in health, behavioural and societal issues indefinitely.

Could our inability to process the reality of our traumatising experiences be related to the fact that we perceive ourselves and everybody else in the world to be completely autonomous?

If we could better perceive the illusions of our sense of self and autonomy, the limits of human control, and how we actually operate as living organisms, could we better accept the traumatising reality of our experiences without resentment, judgement and helplessness?

Regaining a Healthy Sense of Optimism

By understanding how we function as an organic living being rather than as a free autonomous agent, we can better equip ourselves to accept whatever comes our way, understanding that the most effective way to maximise the chances of positive outcomes is to be socially successful.

We can improve the way we perceive and form opinions of ourselves and other people based on the knowledge that nobody is inherently good or bad. We can also understand and forgive ourselves in order to stop perceiving our illusory sense of self as undeserving, allowing us to work towards a future that is not necessarily dictated by past thoughts, behaviours or even outcomes.

By seeing through the autonomy illusion, we can unlock our innate sense of optimism that supports our fundamental survival instincts and aids in personal and societal wellbeing.

This article has been adapted from the book, Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation, which explores concepts ranging from neuroscience and evolutionary biology to the latest empirical research in quantum consciousness to dispel the human autonomy illusion and peel back the layers of the bigger picture of our existence. By understanding the illusions created by our minds, how we really operate as humans, and how to reflect objectively, Monothology helps you unlock self-awareness and boost emotional resilience.

Monothology presents a non-religious explanation of ‘God’ as the universe emerging, with our ‘Sense of God’ described through the lens of biology and evolution as an emergent cognitive function. It discusses how existing research suggests this Sense of God could be the origin of both religion and science.

We also explore the nature of free will, personal responsibility, mental health, increasing societal narcissism, and the meaning of life through groundbreaking and established research in neuroscience, evolution, quantum consciousness, particle physics, behavioural psychology, and much more.

Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation is available to purchase now at the Amazon Kindle Store for $9.99.

0 Comments