The awesomely named Chaos Theory implies that given enough information about a seemingly random chaotic system’s initial conditions, we could predict its trajectory – or future – with pinpoint accuracy.

And human beings are chaotic systems, even if we like to believe in the illusion of human autonomy.

According to the Chaos Theory, chaotic systems – which range from weather and stock markets to galaxies – tend to form deterministic patterns that can be described by mathematical formula. However, as the initial conditions are so sensitive in chaotic systems, miniscule miscalculations can result in wildly incorrect predictions. And tiny changes to existing chaotic systems can produce wildly diverse results.

In practice, Chaos Theory implies that predicting the outcomes of any chaotic system with certainty is virtually impossible, even if we can get extremely close.

But statistically speaking, ‘extremely close’ means nothing to the human experience.

What Is Chaos?

Contrary to widespread understanding, ‘chaos’ doesn’t refer to shock, terror and complete disorder. Instead, as the Merriam-Webster Dictionary describes it, chaos is ‘the inherent unpredictability in the behaviour of a complex natural system.’

In the context of the Chaos Theory, chaos can refer to complex systems that exhibit seemingly unpredictable or ‘random’ behaviours despite being governed by deterministic laws.

The Butterfly Effect

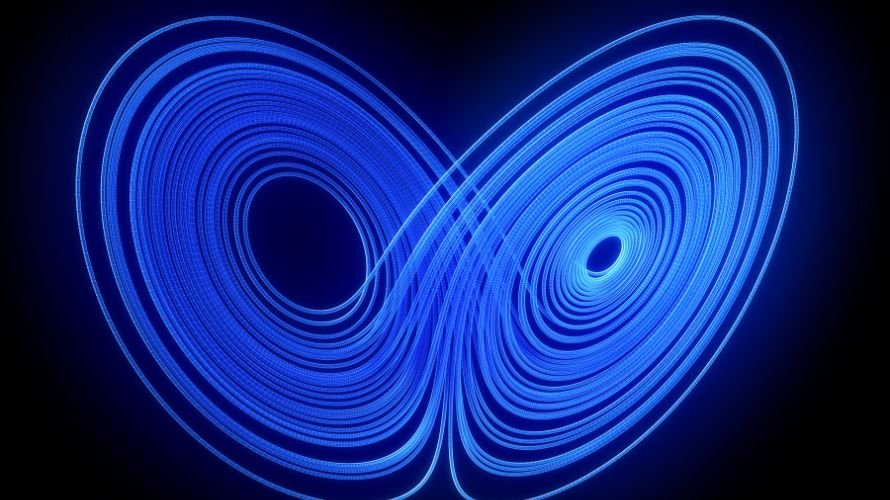

In 1961, meteorologist Edward Lorenz created a mathematical model in an attempt to accurately predict the weather using the latest tech – an early computer.

Lorenz supplied his model with data representing the current weather conditions, allowing him to predict the weather a few minutes in advance. By repeatedly feeding these predictions back into his model, he could generate forecasts for days and even weeks in advance.

When re-running a forecast, he used a prediction from about halfway through the original forecast run as the starting point. Without realising his computer was making calculations using numbers to six decimal places, Lorenz started the re-run with a number to three decimal places. Specifically, he started the re-run with 0.506 instead of 0.506127 – that’s a difference of just one part in a thousand. Even though he started the re-run with virtually identical conditions, the predictions produced by the original forecast and the re-run were wildly different.

Lorenz famously illustrated these results with the Butterfly Effect analogy – that the flap of a butterfly’s wings can cause a hurricane on the other side of the planet (paraphrased).

In a chaotic system, tiny alterations can produce dramatic changes.

Chaos in Our Daily Lives

Chaotic systems are prevalent in our daily lives. Human civilisation itself is a chaotic system that’s highly sensitive to initial conditions (single innovations lead to widespread changes, wars between previously peaceful nations escalate quickly).

Interactions between individuals lead to emergent behaviours and phenomenon ranging from political movements to cultural trends that are virtually impossible to predict.

Examples of chaotic systems that have significant impacts on our daily lives include stock markets, city infrastructures, economic systems – and all social interactions.

The better we know the initial conditions of these systems or events, the better we can predict the outcomes. But the conditions are so sensitive and multi-faceted that predicting them with accuracy is virtually impossible – especially considering all the factors that can change the nature of these systems after the initial conditions are set.

Are We All Chaotic Individuals?

The Chaos Theory isn’t just a practical tool we can use to predict things like the weather, population dynamics and potential stock market fluctuations.

According to Yanagisawa, H. (2022), Chaos Theory can be used to describe the complex, dynamic nature of mental processes and behaviour.

Elements of thinking directly apply to the Chaos Theory – our thought processes, decisions and behaviours are incredibly sensitive to initial conditions and new inputs. A slight change in emotional state can lead to drastically different outputs.

If consciousness is a quantum mechanical process as theorised by the Orch-OR theory (which suggests consciousness arises from coherent quantum events in our brain’s support structures), it’s fair to say that it is one of the most complex and unpredictable quantum systems in the universe.

What Does Quantum Mechanics Have to Do with Anything?

Many scientists believe that all cosmic phenomena, including human decision-making, may be explainable at the quantum level. If our brains really are super-computers as the latest research on quantum consciousness suggests, then quantum mechanics can tell us whether the future is predetermined or not. It might also shed light on how predictable our universe is if it is probabilistic.

Read our full article on free will and quantum mechanics to discover the fascinating inner workings of our reality through GTA analogies and mind-bending thought experiments.

For now, let’s focus on the fact that the Chaos Theory implies that we could predict the future trajectory of all chaotic systems if we had enough information.

Hypothetically if we paused time right now; assuming we had data on every aspect of history so far, we could predict the future accurately. The wheels are already in motion – people are already on their way and pressing unpause simply allows them to continue. However, if one person changed their decision in the next second, then our future would look very different, as demonstrated by the butterfly effect analogy.

In other words, all potential outcomes may be predetermined – but we’ll only experience one of them.

So, can the future be predetermined and probabilistic at the same time?

Our article on free will and quantum mechanics details how the Many-Worlds Interpretation makes determinism and probabilism theoretically possible.

For now, the key takeaway is that, if all this is true, our future is highly predictable (if we had access to enough information about an event’s initial conditions), but not set in stone.

So, if everything is explainable at the quantum level, our brains are quantum computers, and the future is probable but not definitive, how predictable is it?

The Accuracy of Quantum Event Predictions

In general, macroscopic quantum events are more predictable than microscopic events. For example, the behaviour of a collective of coherent quantum particles, such as superconductive electrons in copper pairs, is so predictable that it is virtually deterministic. However, our predictions are less accurate when it comes to predicting an individual electron’s spin before measuring it.

Therefore, we can predict only the probability distribution of possible outcomes, not the exact outcome of any single event.

Applying this to the human experience – if somebody were to know by heart your entire life story, they would be able to predict your decisions with relative accuracy based on your perceptions, experiences and goals. But even with this information, there is room for error – unforeseen circumstances, for example, might have a temporary effect on your typical behaviour. I.e., you might drink a cup of tea every morning as a wake-up ritual. But if you didn’t sleep well and have an endless to-do list for the day, you might choose a coffee instead.

Sophisticated data analysis software can relatively accurately predict the outcomes of widespread human behaviours. For example, algorithms can forecast market trends, consumer purchasing patterns, and even voting behaviours with a high degree of accuracy by analysing large datasets that aggregate individual decisions and behaviours. Nevertheless, tiny differences in predictions can reflect dramatic differences in outcomes.

What Does This Mean for Us?

Even if the probability distribution of our possible outcomes is statistically limited (i.e., 99.999999% of human outcomes might already be ‘determined’), the tiny fraction we have control over still represents a broad (probably infinite) spectrum of possibilities.

In the grand scheme of humanity, destroying the world tomorrow or in 1,000 years through nuclear apocalypse represents an insignificant difference to our entire trajectory. It makes an imperceptibly negligible difference to the grand scheme of the entire universe’s emerging. But it makes a great deal of difference to our individual and collective lives, including those of future generations.

But how much control do we actually have over our own lives? Read our article on the autonomy illusion to find out how you can begin retaking as much control as you do have. Your mind doesn’t control your body in the way you perceive – it’s much more nuanced than that. Realigning your perceptions can do you a world of good.

As the Chaos Theory shows, tiny changes can bring dramatic results.

You can read more about the latest research on the neuroscience of volition to find out about what control we have over our decision-making process and potential outcomes.

For now, we’ll leave you with a few macroeconomic statistics so that you can ponder the probability distribution of our collective future.

The Probability Distribution of Our Potential Futures

In the best-case scenario on a macroscopic scale, we fix all the world’s major problems. Let’s briefly look at whether that’s realistic cost-wise:

- The UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) claims that successfully fighting climate change in all developing countries would cost $7 trillion per year from 2023 to 2030 (more after).

- The UNCTAD also states that providing universal access to primary and secondary education in 48 developing countries would cost $5.9 trillion per year.

- A 2020 study by organisations including Cornell University and the FAO suggested it would cost $330 billion in total to end world hunger by 2030 (the number to end world hunger in ten years from now would now be higher).

- Back in 2017, the WHO estimated that the cost of universal health coverage would increase to $371 billion per year by 2030.

As an incredibly rough estimate, we’d need to spend an extra $13.6 trillion per year (we’ve included the world hunger figure as an annual fee for simplicity) to ensure just about everybody in the world had access to food, education, healthcare, and a future. Given that estimates for the likes of infrastructure and logistics can often be wildly inaccurate, let’s say it would cost – at least until innovations reduced prices (potentially significantly) – $20 trillion per year for the foreseeable future.

To see how realistic this trajectory is in terms of potential futures, let’s take a quick look at some current trends:

- According to some estimates, the top 1% have increased their wealth by $42 trillion over the past decade.

- The UBS Global Wealth Report 2023 estimates that the world’s top 1.1% of wealthiest people now control to a total of around $208 trillion (45.8% of the world’s total wealth).

- The global economic impact of violence is astonishing and rising. For example, it was $13.6 trillion in 2015, $14.96 trillion in 2020, and $19.1 trillion in 2023.

- Fossil fuel financing exceeds $1 trillion per year.

- The world’s nine (official) nuclear powers spend $91 billion per year on their nuclear arsenal.

- According to the US Government Accountability Office, the US Government lost nearly $2.4 trillion in payment errors over the previous two decades.

- About 1.3 billion tonnes of food is wasted per year (about a third of all food for human consumption).

- Wall Street banks continue to give out bonuses estimated at well over $30 billion per year.

- If the world’s richest people gave more of their personal profits away in taxes and contributions, those people would remain the world’s richest people.

- Many studies suggest that the technology to address many of our urgent environmental problems already exists.

Based on the above data, the probability distribution of our future is rather wide. Best case scenario, most of the world’s major macro problems are solved within a decade because all our basic needs are met.

Worst case scenario, most of the world’s major macro problems are solved within a decade because we no longer have basic needs.

The reality, of course, will likely be somewhere in between. Our individual and collective perspectives will be a significant determining factor.

We’re told widescale change that benefits everybody is too complex. There are too many factors at play, from market dynamics, government priorities, debt and lack of political will to political instability, armed conflicts, low income levels, supply chain disruptions and discrimination. They all come down to the same thing…

Maintaining the current trajectory is also intricately complex. Complexity isn’t the problem…

This article has been adapted from the book, Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation, which explores concepts ranging from neuroscience and evolutionary biology to the latest empirical research in quantum consciousness to dispel the human autonomy illusion and peel back the layers of the bigger picture of our existence. By understanding the illusions created by our minds, how we really operate as humans, and how to reflect objectively, Monothology helps you unlock self-awareness and boost emotional resilience.

Monothology presents a non-religious explanation of ‘God’ as the universe emerging, with our ‘Sense of God’ described through the lens of biology and evolution as an emergent cognitive function. It discusses how existing research suggests this Sense of God could be the origin of both religion and science.

We also explore the nature of free will, personal responsibility, mental health, increasing societal narcissism, and the meaning of life through groundbreaking and established research in neuroscience, evolution, quantum consciousness, particle physics, behavioural psychology, and much more.

Monothology: A Grassroots Science-Based Philosophy in ‘Self’ Transformation is available to purchase now at the Amazon Kindle Store for $9.99.

0 Comments